Variously known as the “The Human Vacuum Cleaner,” “Mr. Hoover,” or “Mr. Impossible,” Brooks Robinson set the standard for defensive wizardry at third base, winning a record 16 consecutive Gold Gloves thanks to his combination of ambidexterity, supernaturally quick reflexes, and acrobatic skill. He was an 18-time All-Star, a regular season, All-Star Game, and World Series MVP, and a first-ballot Hall of Famer. More than that, he was “Mr. Oriole” for his 23 seasons spent with Baltimore, a foundational piece for four pennant winners and two champions, and a beloved icon within the community and throughout the game. In 1966, Sports Illustrated’s William Leggett wrote that Robinson “ranked second only to crab cakes in Baltimore.” He may have surpassed them since.

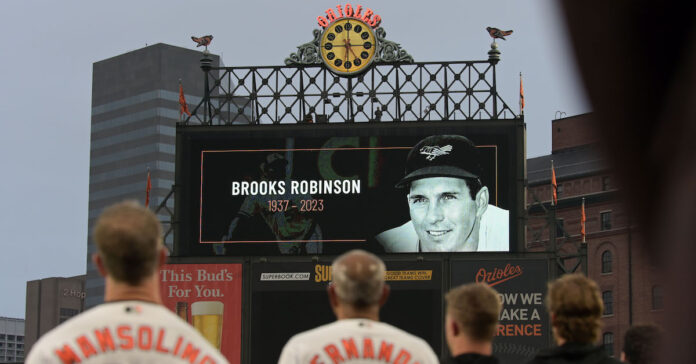

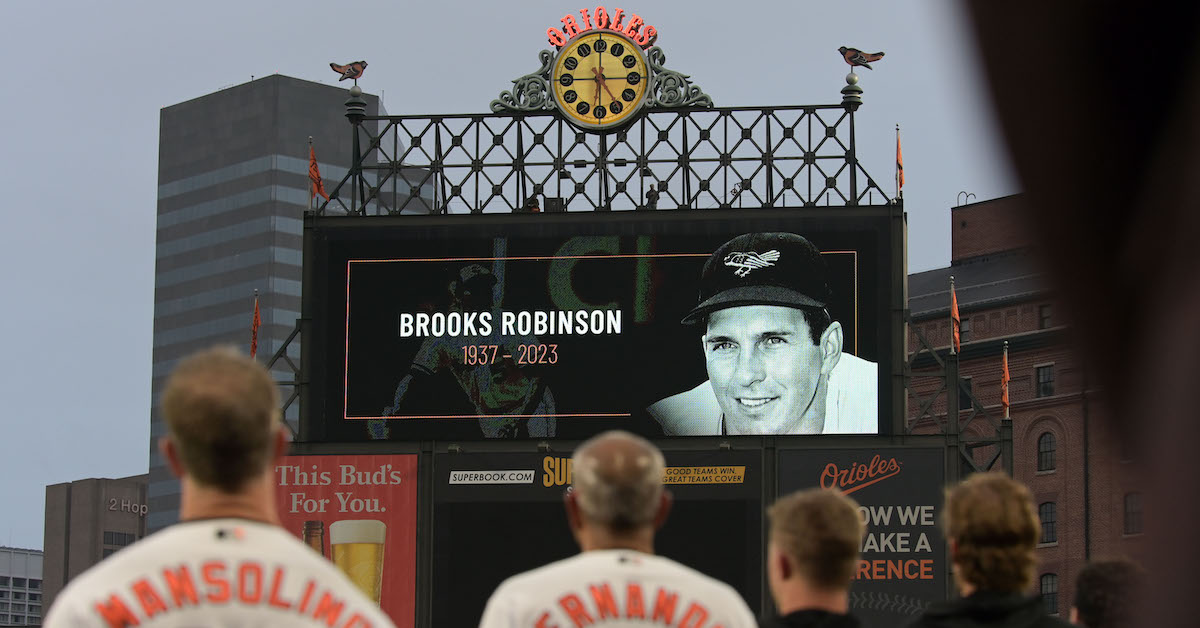

Robinson died on Tuesday at the age of 86. According to his agent, the cause was coronary disease. On the broadcast of the Orioles’ game on Tuesday night, longtime teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Jim Palmer fought back tears to pay tribute. “We all know he’s a great player, he won 16 Gold Gloves, but we also know how special a person he was,” said Palmer, who like Robinson debuted with the Orioles as a teenager, spent his entire career with the team, and was elected to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. “I think as a young player you make a decision early in your life, ‘Okay, who do I want to emulate? Who do I want to be like?’ Brooks was that guy.”

Indeed, Robinson the person was even more revered than Robinson the player. Wrote the Washington Post’s Thomas Boswell on the occasion of the third baseman’s 1983 induction to the Hall:

The part of Robinson that will be hardest to transmit to posterity will be his upright character, his manly gentleness, his constant consideration for others, his knack of blending candor with kindness. In an age seemingly committed to exposing every foible of a public figure, Robinson — almost alone among baseball players — was accepted as a kind of natural nobleman. “People love Brooks because he deserves to be loved,” said Manager Earl Weaver.

Robinson spent his entire major league career with the Orioles, debuting in 1955 as an 18-year-old and retiring late in the ’77 season at the age of 40. Though rarely a spectacular hitter, he totaled 2,848 career hits and 268 homers to go with a .267/.322/.401 (105 OPS+) batting line. He made 18 All-Star teams (including two a year from 1960–62) and set a record for position players with his 16 straight Gold Gloves (from 1969–75); only pitcher Greg Maddux won more (18), while pitcher Jim Kaat equaled Robinson’s total. In 1964, he won AL MVP honors by hitting .317/.368/.521 (145 OPS+) with 28 homers and leading the league with 118 RBI and 8.1 WAR.

The pinnacle of Robinson’s career was the 1970 World Series, when he etched himself into the national consciousness with his outstanding, MVP-winning performance on both sides of the ball against the Reds. He hit for a .429 average with two homers and six RBI in the Orioles’ five-game triumph, and with his diving stops and improbably accurate throws across the diamond, produced some of the most memorable and oft-aired highlights of any Fall Classic.

“I’m beginning to see Brooks in my sleep,” said Reds manager Sparky Anderson afterwards. “If I dropped this paper plate, he’d pick it up on one hop and throw me out at first.”

Robinson additionally helped the Orioles win the 1966 World Series as well as pennants in ’69 and ’71, with division titles in ’73 and ’74 as well. He hit .303/.323/.462 in 156 plate appearances in his postseason career, and even with a 1-for-19 performance in a losing cause against the Mets in the 1969 World Series, carried a reputation as a clutch hitter. But for all of his accomplishments, he was hardly a five-tool standout. He lacked foot speed and bat speed, and had neither great power nor a particularly strong arm; in fact, he was a natural left-hander who learned to throw right-handed in his youth, and built up his arm by throwing newspapers on a delivery route that included Hall of Fame catcher Bill Dickey. His play at the hot corner was unorthodox, as the Chicago Daily Herald’s Mike Klein explained in 1973 (h/t Mark Simon):

“It’s a cardinal rule of baseball that any successful infielder crouch low, keep his head down and glove close to the ground. ‘Play the ball; don’t let the ball play you.’

“But Robinson, and this attests to his great quickness (different from speed, which he lacks) plays higher than most brothers of the Hot Corner Fraternity. His crouch is less pronounced. Playing down at shell city means attack and charge the ball. Which he does to perfection.

“There’s even a worked-up set of Brooks Robinson footsteps for making sure he pivots off the left foot when fielding bunts. What makes his golden magnetic glovework so intriguing however is that Robinson going backwards and to either side will make a better play than most third basemen playing it by all the rules. It is distinctly Robinson.

“Nobody else does it quite the same.”

Brooks Calbert Robinson was born on May 18, 1937 in Little Rock, Arkansas. His father, Brooks Robinson Sr., was a fireman who played semiprofessional baseball, while his mother, Ethel Mae (Denker) Robinson, was a clerk at the Arkansas State treasury department. The elder Robinson introduced the game to his son, sawing off a broomstick to use as a bat, hitting him groundballs, and employing him as his team’s batboy. The younger Robinson listened to the Cardinals on the radio growing up, and when he was 12 years old, wrote a school composition assignment on his ambition to play third base for the team.

At Little Rock Central High School — which two years after his 1955 graduation would become famous for its Supreme Court-ordered desegregation — Robinson starred in basketball, earning all-state honors as a junior. He played football as well, but the school did not have a baseball team, so he followed in his father’s footsteps by playing with the city’s American Legion team, the Little Rock Doughboys. His glovework drew the attention of Lindsay Deal, a scout who had a brief cup of coffee with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1939 and was a former teammate of Paul Richards, who took over as the manager and general manager of the Orioles in 1955, a year after their inaugural season in Baltimore (they had been the St. Louis Browns prior). “He’s no speed demon, but neither is he a truck horse,” wrote Deal in a letter to Richards. “Brooks has a lot of power, baseball savvy, and is always cool when the chips are down.”

The Orioles, Reds, and Giants each offered Robinson a $4,000 bonus to sign, with all but the last of those teams offering major league contracts as well. Robinson chose Baltimore, signing two days after graduating from high school in May. Scout Arthur Ehlers convinced him that the organization’s low standing (they had finished seventh at 54-100 in 1954) offered Robinson a quicker path to the majors. That turned out to be correct, in that after hitting .331/.415/.489 with 11 homers in 95 games for the York White Roses of the Class B Piedmont League, he was called up. In his major league debut on September 17, 1955, Robinson went 2-for-4 with singles off the Senators’ Chuck Stobbs and Webbo Clarke, driving in a run via the latter. At 18 years and 122 days old, he remains the second-youngest position player to debut with the Orioles since their move to Baltimore.

Those were the only two hits Robinson collected in 22 PA in the majors that year. He spent all but 15 games of the 1956 season with Double-A San Antonio, collecting his first major league homer off the Senators’ Evelio Hernández on September 29. He made the Orioles’ Opening Day lineup in 1957 but tore cartilage in his knee two weeks into the season, missed two months, and spent over a month rehabbing at San Antonio before returning to the majors. He hit just .239/.286/.359 with two homers in 50 games that year.

With incumbent third baseman (and future Hall of Famer) George Kell retiring after the 1957 season, Robinson finally spent a full year in the majors in ’58. Alas, his dismal performance (.238/.292/.305, 69 OPS+) and then a slow start in 1959 — fallout from a winter stint in the Army National Guard, and a late arrival to spring training — led to a return trip to the minors, in this case Triple-A Vancouver. Upon being recalled, he got hot over the season’s final two months and finished with a respectable .284/.325/.383 (97 OPS+) line in 88 games. He was in the major leagues for good.

Robinson broke out in 1960, his age-23 season. He hit .294/.329/.440 (108 OPS+) with 14 homers, and began All-Star and Gold Glove streaks. His 4.1 WAR ranked sixth in the league (though of course the metric was about half a century away from being invented), and he finished third in the AL MVP voting behind Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle. The Orioles went 89-65 and finished second in the AL, the franchise’s first season above .500 since 1945 (they went 76-76 in 1957).

The 1960 season began a five-year stretch in which Robinson hit well in even-year seasons but was slightly subpar in odd-year ones, though defense always bolstered his value. After hitting for a 98 OPS+ with just seven homers in 1961, he set career highs for himself across the board with a 126 OPS+ (.303/.342/.486) performance with 23 homers and a league-leading 6.1 WAR in ’62. After a tepid 1963, he had what would stand as the best statistical season of his career in ’64 while helping the Orioles to 97 wins under first-year manager Hank Bauer. He was a near-unanimous choice as the AL MVP, receiving 18 of 20 first-place votes.

Robinson followed that great 1964 season with third- and second-place finishes in the MVP voting thanks to more consistency at the plate. In the second of those seasons, 1966, he was joined by Frank Robinson via a trade from the Reds. The newcomer had been the NL MVP half a decade earlier but was viewed as “an old 30” in the words of Reds owner Bill DeWitt. The Orioles had never had a Black star before, and they already had a clubhouse leader in their third baseman, but concerns about how the incoming Robinson would be received were allayed when the incumbent one greeted him at the batting cage by telling him, “Frank, you’re exactly what we need.” On Opening Day, after the Red Sox’s Earl Wilson hit Frank with a pitch in his first plate appearance as an Oriole, Brooks followed with a two-run homer. “The Act,” as Sports Illustrated termed the pairing of the Robinsons, quickly became a smashing success.

Frank’s firebrand play put a stamp on the Orioles as he won the AL Triple Crown and MVP honors. The Orioles won their first pennant, then faced off against the Dodgers, the reigning champions, in the World Series. The Robinsons hit back-to-back home runs off Don Drysdale in the first inning of the opener and didn’t trail for a single inning as the Orioles pulled off a shocking four-game sweep.

Thanks to above-average offense and off-the-charts defense — Total Zone ratings of 32 and 33 runs — at a time when pitching was becoming ever more dominant, Robinson was runner-up to Carl Yastrzemski on the AL WAR leaderboards in both 1967 (7.7) and ’68 (8.4), though the Orioles couldn’t repeat as AL champions. At the All-Star break in 1968, Bauer was fired, replaced by Weaver, and thanks to a late charge the Orioles won 91 games and finished second.

They were just getting started under Weaver. With each league split into two divisions starting in 1969, the Orioles began a run of dominance in the new AL East, winning a total of 318 games over a three-season span as well as three AL pennants. Robinson hit for a modest 105 OPS+ across that stretch but still averaged 20 homers and 4.7 WAR. After beating the Twins in the 1969 ALCS, the Orioles were upset by the Miracle Mets; Robinson, who had gone 7-for-14 in the ALCS, was held to just one hit, though twice he drove in the Orioles’ only run in 2-1 losses, no small feat for a team that scored just nine runs in five games.

After going 7-for-12 in the Orioles’ three-game sweep of the Twins in 1970, Robinson took over the World Series against the Reds from the outset. In the sixth inning of the opening game at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium — the first outdoor ballpark with Astroturf — Robinson set the tone with his stop of a hot smash off the bat of Lee May down the third base line. Robinson backhanded the ball while lunging into foul territory, and with his momentum still carrying him to his right threw a high, arcing one-hopper to Boog Powell at first base in time for the out. Thanks to the confluence of color television and slow-motion instant replay, the play has become one of the most famous in modern World Series history, a mesmerizing spectacle and an archetype for similarly dazzling plays by the likes of Manny Machado and Nolan Arenado in this day and age.

“His arm went one way, his body another, and his shoes another,” said Reds pitcher Clay Carroll of the play. In the next half-inning, Robinson broke a 3-3 tie with a solo homer off Gary Nolan that proved to be the deciding run. In the fourth inning of Game 2, Robinson victimized May again, making a diving stop to his right, spinning, and then starting a 5-4-3 double play (see the top video at the 1:58 mark); he later singled and scored in the midst of a five-run fifth inning that erased a 4-1 deficit. In Game 3, he drove in a pair of first inning runs with a double off Tony Cloninger, ended the top of the sixth with a diving catch of a line drive to his left off the bat of Johnny Bench, and in the bottom of the frame added another double and scored when pitcher Dave McNally hit a grand slam. In Game 4, he went 4-for-4 with another solo homer off Nolan as well as an RBI single in a losing cause. In the ninth inning of Game 5, he dove to spear a foul ball off the bat of Bench, and, fittingly, began the Series-clinching play by fielding a routine grounder by Pat Corrales, then firing to first to give the Orioles their second championship in a five-year period.

Robinson was the obvious MVP of the Series. “If we’d have known he wanted a new car that bad, we’d have chipped in and bought him one,” quipped Bench afterwards. When combined with his 1964 AL MVP award and ’66 All-Star Game MVP award, Robinson was the first player to claim all three honors. Frank Robinson became the second just a year later with his All-Star Game award. Nobody has done it since.

After the Orioles won the AL East again in 1971, Robinson came up big in the ALCS against the A’s, a budding dynasty themselves. In Game 1 he singled against rookie sensation Vida Blue and scored the tying run in a four-run seventh-inning rally that proved decisive. In Game 2, he started the scoring with a second-inning solo homer off Catfish Hunter; the Orioles won again, 5-1. In Game 3, his two-run, bases-loaded double off Diego Segui broke a 1-1 tie in the fifth inning, and he added another double in the seventh as the Orioles completed the sweep. In the World Series against the Pirates, he went 3-for-3 with two walks and three RBI in an 11-3 win in Game 2 but was otherwise comparatively quiet in the seven-game classic, which the Pirates won.

Wanting to find space for the up-and-coming Don Baylor, the Orioles traded the 36-year-old Frank Robinson to the Dodgers after the 1971 season. Subsequent Orioles teams weren’t as strong, and neither was Brooks. Though he totaled 11.0 WAR from 1972–74, he produced just one above-average season with the bat, in the last of those years. With Baylor and second baseman Bobby Grich providing a much-needed injection of youth, the Orioles won back-to-back division titles in 1973 and ’74, but they couldn’t get past the A’s in the ALCS in either year.

After hitting a dismal .201/.267/.274 in 1975 — still a season in which he was 18 runs above average defensively en route to 1.8 WAR — and struggling at the plate into 1976 as well, Robinson was finally supplanted as the regular third baseman by 25-year-old Doug DeCinces. He spent 1977 as a player-coach, setting a record for 23 consecutive seasons with one team (Yastrzemski later tied it), but he played sparingly. He pinch-hit a three-run walk-off off Cleveland’s Dave LaRoche in the 10th inning on April 9; it was his 268th and final home run.

On August 21, with the team facing a roster crunch, Robinson retired as a player. “Despite the logic of the move, it was a very difficult decision to make, considering Brooks’s tremendous achievements and the love we all have for him,” said general manager Hank Peters. “He has been, unquestionably, the Orioles’ most important and most beloved player and he never will be replaced in the hearts of his countless fans.”

A month later, the Orioles paid tribute with a pregame ceremony that included retiring his no. 5. They drove Robinson around the field in a 1955 Cadillac, representing his first year in the majors, and presented him with a new car, a Hawaiian vacation, and Memorial Stadium’s third base itself. The Rawlings Company gave him replacement Gold Gloves, as he had donated all but two of his original 16 to local charities. May, by this point a teammate, presented Robinson with a vacuum cleaner, referring back to the 1970 World Series as he said, “Everything we hit, you sucked it up. And you’ll notice, Brooks, that just like you, this machine has a lot of miles on it.”

In 1978, Robinson joined the Orioles’ broadcast booth, a role he would remain in through ’93. He could not afford to retire to a life of leisure, as he made less than $1 million in salary in his entire career, and wound up broke in 1976 when his sporting goods store was overextended. He became a regular on the baseball card show circuit (this scribe got his autograph at the 2002 All-Star Game Fan Fest), and was involved in numerous businesses, lending his name to products and serving as a spokesman for Crown Petroleum. Later he was involved in a group that owned four minor league teams, including one in York, Pennsylvania, where he began his professional career.

Robinson was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1983, receiving 92% of the vote and becoming the first third baseman to be elected by the BBWAA in his first year of eligibility — and just the third they had elected at all in 48 years. To that point, only Ty Cobb, Henry Aaron, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Willie Mays, Bob Feller, Ted Williams, and Stan Musial received higher shares of the vote, though today Robinson ranks 28th in voting share. He was inducted alongside Juan Marichal, Walter Alston, and Kell, the fellow Arkansas native who had served as his mentor with the Orioles in 1957.

In terms of advanced statistics, Robinson ranks seventh among third basemen in career WAR (78.4), 11th in seven-year peak (45.8), and eighth in JAWS (62.1), with five of the seven players above him in the last of those categories hailing from more recent eras. Not surprisingly, his standing is driven by the estimate of his defensive value, which is based on data admittedly less sophisticated than we have today. He’s first among third basemen in Fielding Runs (Total Zone and Defensive Runs Saved) by a country mile:

Third Basemen Career Fielding Runs Leaders

SOURCE: Baseball-Reference

Includes runs via Total Zone (through 2002) and Defensive Runs Saved (since 2003) for players who spent at least 85% of their careers at third base.

Additionally, Robinson is third all-time among all fielders in dWAR, the total defensive value that includes both Fielding Runs and positional adjustments:

Career Defensive WAR (dWAR) Leaders

SOURCE: Baseball-Reference

Includes Fielding Runs (Total Zone and Defensive Runs Saved) plus positional adjustments. * = Does not include framing runs.

If there’s an advertisement for the Oriole Way, whose foundation was laid by Richards and maintained by his successors, it’s here. Not only did the homegrown Robinson and Belanger form the best defensive left side of any infield for a period of over a decade, but Aparicio preceded Belanger as the team’s regular shortstop from 1962-66. Ripken was the son of a career minor leaguer who served as the backbone of the organization as a coach and manager; Cal Ripken Sr. managed Belanger at A-level Aberdeen in 1964.

Anyway, longevity obviously has something to do with Robinson’s standing — in fact, his 2,896 games played ranked fifth when he retired and is still 16th — but it’s also notable that he never started a game at another position, and played just 47.1 innings elsewhere, switching to second or shortstop in late-inning situations early in his career. He never played first base or DH, and provided significant defensive value at third for as long as he held the regular job.

“I don’t think anybody will care what I did here 20 or 25 years from now,” said Robinson with typical humility to Sports Illustrated’s Mark Kram in 1970. Yet more than half a century later, people still do care, not only about the feats Robinson accomplished on the field but about the way he carried himself off of it. That’s quite a legacy.