Way back when, pitchers threw mostly fastballs, especially down and away. They didn’t like pounding the zone with first pitches. They didn’t dare throw nonfastballs at the top of the zone. They took as much time as they wanted between pitches and they threw to catchers who set targets with a squatting position that had not changed much since Gabby “Old Tomato Face” Hartnett was behind the dish 100 years ago.

Way back … when? That was only 2015.

The point is baseball changes faster than ever. Its fluidity is accelerated by the growing amount of information available and how quickly it is evaluated and shared.

Pitching changes faster than hitting. That’s because pitching, like hitting a golf ball, initiates action. It happens in its own vacuum. Hitting reacts to the variables pitching sets into motion.

Pitching in 2023 was vastly different than it was in ’15, the start of the Statcast era, when advanced pitch-tracking data became mainstream. And it’s not just because of the pitch timer.

Advances in technology (Trackman, Rapsodo, etc.), training (weighted balls) and baseball ops (“run prevention” specialists to assist coaching staffs) have created unparalleled pitching depth when it comes to throwing harder and smarter.

For example, the number of pitchers who can throw 100 mph has gone up 31% since 2015. But you’re talking only 64 elite arms, or about two per team. The greater impact comes from how information is applied by all teams and all pitchers. Put another way: Better training is leading to more velocity. But better technology is leading to better pitch shapes and sequencing.

The game is played much differently today than even a few years ago. Sometimes it happens so fast you barely notice. With 2023 behind us, it’s time now to take a snapshot. Here are the six biggest pitching trends of the past year.

1. Pitching is better than ever.

Bold statement, I know. Nobody throws complete games, guys get hurt all the time, the average team burns through 29 pitchers every year, the Oakland A’s, blah, blah, blah.

But if you’re talking about only the pure quality of the stuff—how difficult it is to hit—I believe it to be true.

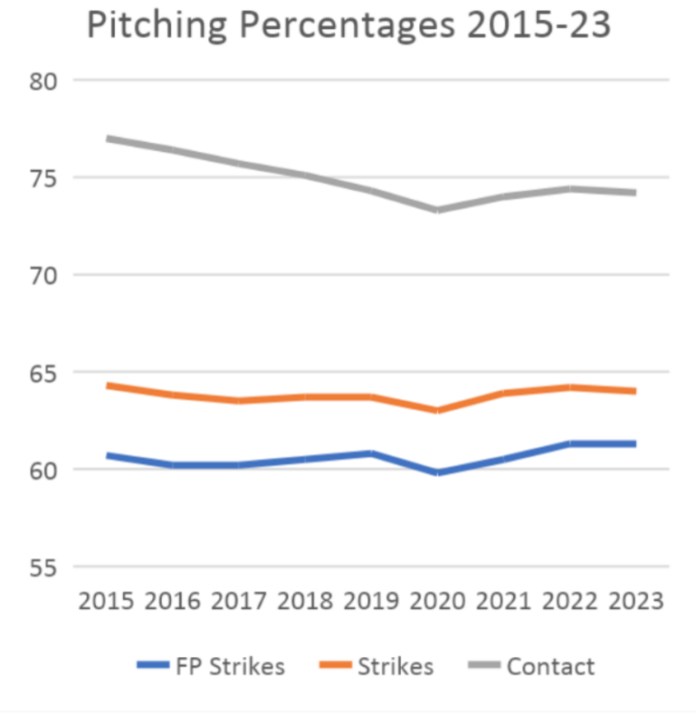

Below are the major rate trends of the past eight years: first-pitch strike percentage, strike percentage and contact percentage. (You can see the blip the 60-game season of 2020 caused). Generally, pitchers are attacking the zone more and allowing much less contact.

Baseball Savant

2. Pitchers are throwing the most first-pitch strikes in recorded history.

Pitchers threw as few as 55.6% first-pitch strikes in 1991. For the past two seasons, that rate has been 61.3%, the highest since pitch tracking data began in ’88.

It wasn’t until 2013 that first-pitch strike percentage consistently exceeded 60%, and it’s been creeping up since.

Why the new emphasis on first-pitch strikes? I’ll go back to a conversation I had with Rays pitching coach Kyle Snyder this summer. The key to pitching is count leverage. And the key to count leverage is to get ahead in the zone so you can expand out of the zone for your outs. And because pitchers have such good stuff now, they can be more confident about pounding the zone with first-pitch strikes.

Take an old-school guy like Max Scherzer as an example. When Scherzer won his first Cy Young Award in 2014, he threw 63.2% first-pitch strikes. This year, at age 39, he led the majors with 71.4% first-pitch strikes.

To reinforce pounding the zone with a first pitch, Snyder provides this statistical nugget to his pitchers: If you throw a first pitch in the zone, 94% of the outcomes are positive for the pitcher (a strike or an out). I used that on air one night and immediately got texts from people who swore they must have heard me wrong.

Ninety-four percent? Yes, really. Check it out:

2023 First Pitch Strike Outcomes

| Outcome | Rate |

|---|---|

Called strike | 50% |

Foul | 18% |

Swing and miss | 14% |

Out | 12% |

Hit | 6% |

3. Pitchers are throwing more spin and fewer fastballs.

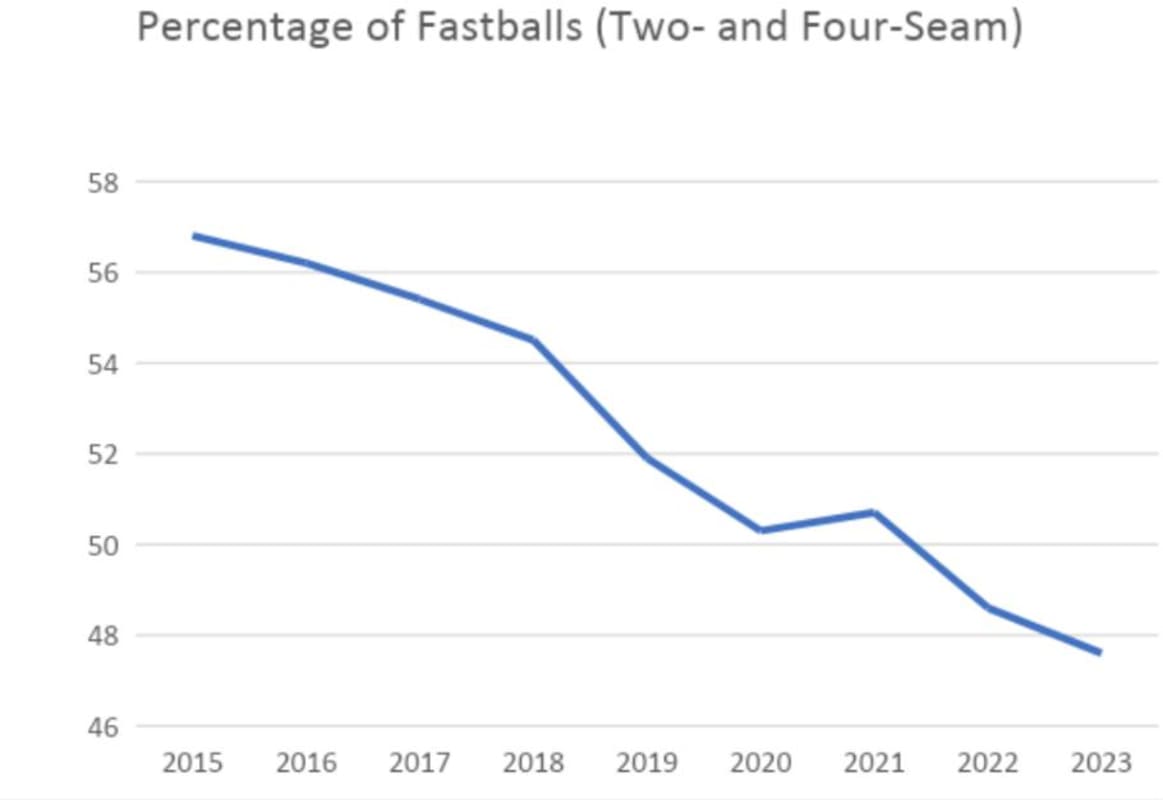

You might have been aware of this in recent years, but what’s new is that the more-spin/fewer-heaters model has boomed over just the past two seasons.

As an example, Texas reliever Josh Sborz throws his fastball at 97 mph with elite spin properties. But he changed from a guy in 2022 who threw 52% four-seamers and 48% breaking pitches to a 36%/64% mix in ’23. Why? “Major league hitters can time a bullet,” he told me.

It’s happening all over baseball. Fastballs have become secondary pitches. The quick explanation is that hitters bat .268 and slug .446 off fastballs and bat .231 and slug .385 against everything else.

In 2023, the sweeper became the Pitch of the Year. It’s essentially a slider with more horizontal break to it, but pitch metrics have become so specific that pitchers regard it as a unique pitch, not just nomenclature. Pitchers rushed to the pitch to fill that gap between a true slider and curveball, adding to the decline of fastballs.

Don’t tell your favorite hitter that in the past eight years, 56,998 fastballs have disappeared from the game—replaced by pitches with movement and spin. They already know how tough it is to hit. Those numbers, and this chart, only highlight the pain.

Baseball Savant

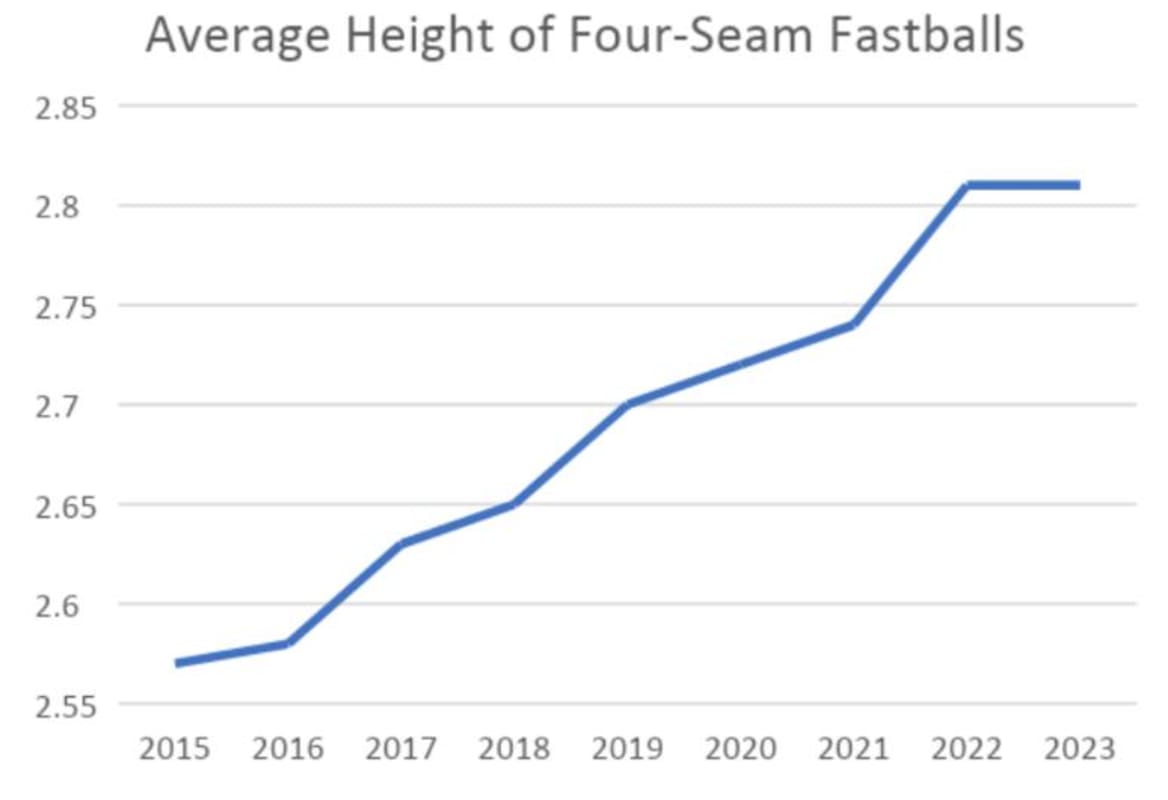

4. Four-seam fastballs are getting higher.

The average height of a four-seam fastball climbed every year for seven straight years before leveling off this year. Pitchers have been working fastballs higher and higher in the zone as new measurements such as induced vertical break and vertical attack angle give specs to what had been oral traditions such as “ride” and “hop.”

Baseball Savant

What do those numbers mean in real terms? Here’s an example. First up is Freddie Freeman hitting a home run in 2016 on a four-seamer at average height that year (2.58 feet off the ground). On the left, note the catcher’s target—and his old-school squatting position. On the right see how the pitch is on target and about low thigh-high. It’s also crushed by Freeman.

Now here is Freeman swinging through a four-seam fastball in 2023 at average height this year (2.81 feet). On the top, note how the catcher’s target has moved higher and how the now-standard one-knee position has replaced the squat. On the bottom, note how the pitch is at the top of the thigh, and Freeman’s barrel passes under it.

Doesn’t seem like much, right? The difference in height is only about three inches. But those three inches mean a 23-point difference in batting average and a 62-point difference in slugging.

2023 Hitting vs. Four-Seam Fastballs by Height

| Feet Off Ground | AVG | SLG |

|---|---|---|

2.5–2.6 (2016 average) | .295 | .531 |

2.8–2.9 (2023 average) | .272 | .469 |

5. Hitters are adjusting to high heat.

A bit of good news for hitters. The more hitters see high fastballs, the more they learn to adjust their swings to hit them.

Guys are hitting off high-velocity machines, $500,000 pitching machines with a video image of that night’s starting pitcher and laser-guided release points for all of his pitches and machines that spit out foam balls to simulate fastballs with extreme induced vertical break, as the Rangers did to adjust to Cristian Javier and Paul Sewald in the postseason.

Repeated exposure to such pitches is beginning to show some benefits:

Hitters vs. Elevated Four-Seam Fastballs (3′ and Higher)

| Year | AVG | SLG |

|---|---|---|

2021 | .188 | .340 |

2022 | .193 | .333 |

2023 | .195 (highest since 2017) | .349 |

But let’s be honest: those are incremental gains. Hitters have not made enough adjustments to force pitchers to go away from elevated four-seamers. In the past two years, pitchers have thrown more elevated fastballs than in the previous 12 years.

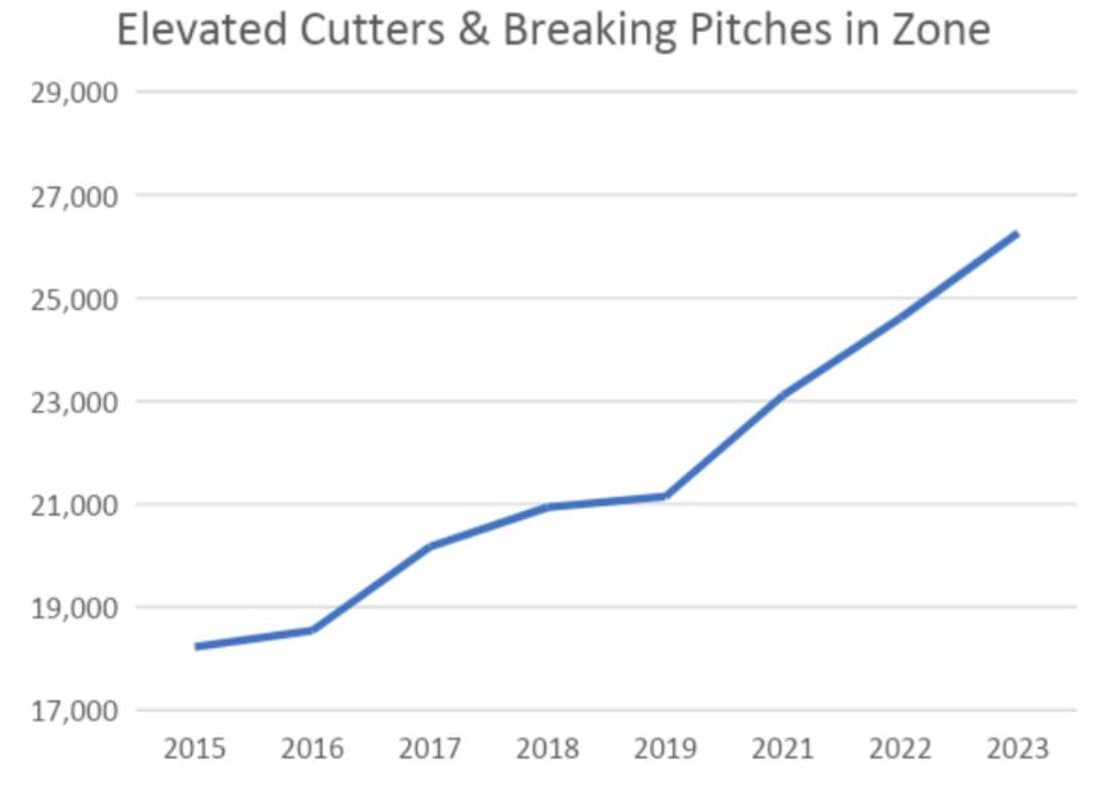

6. Pitchers have created a new weapon: the high breaking ball.

Breaking balls at the top of the zone get hit, right? That was the conventional wisdom, anyway—sort of like the (since disproven) adage about not throwing right-on-right changeups.

Just one problem: It’s not true.

With more fastballs being elevated, pitchers increasingly are tunneling off those elevated heaters with elevated cutters and breaking pitches, especially sliders.

Cutters and breaking pitches in the top third of the strike zone have increased 44% since 2015, including a 24% leap in just the past three seasons. Leaving out the shortened season of ’20 below, this is a serious trend, folks:

Baseball Savant

The foremost practitioners of this trend are Graham Ashcraft of the Reds (cutters and sliders), Rich Hill of the Padres (curveballs and cutters), Clarke Schmidt of the Yankees (cutters and sweepers), Corbin Burnes of the Brewers (cutters), Aaron Civale of the Rays (cutters) and Mitch Keller of the Pirates (cutters and sweepers).

This year hitters got a deserved break with the ban on shifts. Batting average did go up slightly, from .243 to .248. But that’s a rare bit of good news for hitters.

The MLB batting average remained below .250 for a fourth straight year, the longest such stretch since the mound was lowered in 1969. Until 2017, there had never been a season in which games averaged fewer than 50 balls in play; it has now happened seven years in a row.

Make no mistake: We remain in an era dominated by pitching.